A cluster of things

What is a “cluster”? When do things become more than a collection, and turn into something different? Something else?

I am accustomed to thinking about things in terms of homogeneous bags of resources. Whittling down the context a bit more, we’re usually talking about homogeneous bags of compute resources like “CPU”, “storage”. Some reference to the attempts to accurately describe all kinds of compute resources in terms of abstract concepts may be useful, and you would be forgiven if you thought I was referring to Kubernetes here. I have no idea how that word will sound when this bits that make up this page finally rot and it is read the final time, but at the time of writing at the end of the year 2020, Kubernetes is as good a reference concept as I can reliably expect.

This is not a post about Kubernetes. My spell-checker doesn’t even accept “Kubernetes as a real word”, I’m almost prone to writing every instance of it here in monospace.

Kubernetes

Yes, perhaps that’s what it should always look like. Some vaguely technical jargon to remind the reader that we have shared concepts, but not the thing we’re really here to talk about.

No, we are not talking about bags of homogeneous compute resources that we can abstract by function and give names to.

Instead, what I’m writing about here is a bag of distinctly different resources. Little bits of kit that have all kinds of different hardware bits sticking out of them, affixed by pins. What we’re writing about here is the cluster of kit that is uniquely mine: the Raspberry Pis in my office.

Roll call

Let’s get to know them, shall we? I have a Pi 4, two Pi 3Bs and four Pi-Zero W’s at the moment, scattered about the various surfaces of my home office.

While many of them have a dedicated function, some of them have yet to discover theirs.

The Raspberry Pi 4 is a serious little machine. It has a 8x8 multicolour LED array as part of its Sense HAT attached to it, with a dedicated cable and SD attached. I currently use it as my local Vault, and it keeps all my passwords, tokens, certificates, and other secrets.

Next, the two Pi-3s.

These are your average little machines; they’ll get the job done, just don’t expect too much from them. One of them sits attached to the wall on the other end of my office from my desk and has an audio interface to the world: a microphone and speakers are attached to it.

In my mind, it’s the basis for something like a home automation control centre, but I haven’t yet decided how to really go about doing that.

The other Pi3 has an e-Paper display attached to it’s GPIO array and can display simple messages like “Don’t forget the bread” or “You are teh awsom”. The compute and RAM is going a bit to waste on this one too, I suppose one might be able to argue.

The gaggle of Pi-Zeros scattered around the office with a combination of scroll-HAT and surveillance camera functionality. One of them sits directly in front of me and is intended to alert me with a flash of light when impending doom is near.

Another other sits off to the side, with a Ninja pHAT diffuser, and acts as a clock.

The sum of the parts

I find myself adding at least one or two Pis to my my collection every month, and I’ve gotten to the point now where I’m starting to think about how to organise them. Keeping them useful has the attendant need of maintaining and updating them, of shipping software onto them, of ensuring that configuration is applied after having been tested. It’s a playground, yes, but there’s no need to have a messy playground after all.

Before we can bring any sort of higher order to the system, first some order has to be brought at all. This got me thinking, and reminded me of Hashicorp’s Consul. The idea started to seep into my mind that perhaps I could put Consul to use in at least managing the mundane tasks of organising these things on the network, organising services across them.

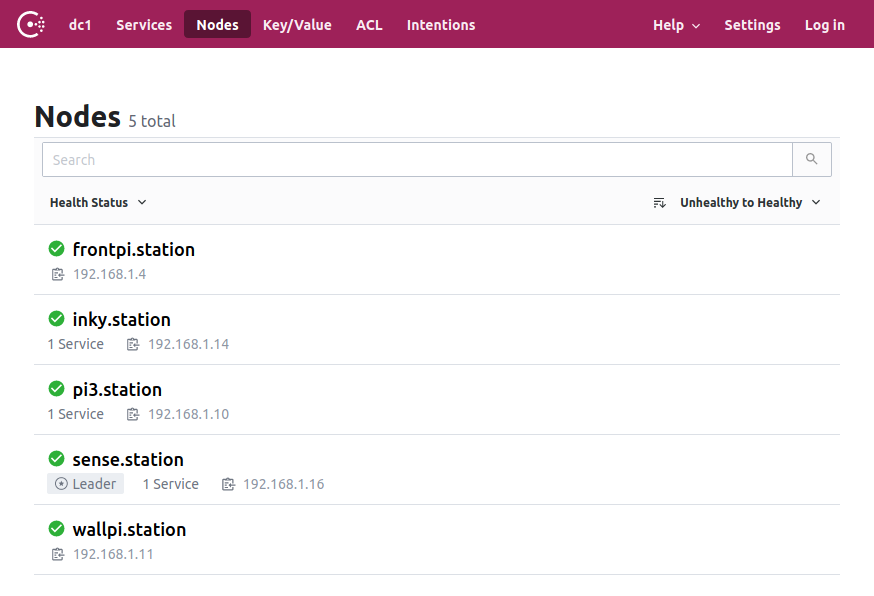

So, I set myself a small goal: Make my gaggle of Pis into a Consul datacentre.

This is the story of how I did that.

A vague form takes shape

In broad strokes, the plan is

- Get Consul on all the bits of hardware

- Configure them:

- Some would be servers

- One of the servers would be a leader

- Some would be agents

- One would be a UI

Achieving this would mean that I would have the good things that a Consul data-centre was designed to deliver:

- Centralized Service Registry: Yes, I want that. Ain’t nobody got time to mess around with manual inventories

- Real-time Health Monitoring: Sure, when I have applications deployed on them, health monitoring, yes, want that.

- Simplified Resource Discovery: Definitely want this. I want to call things by their name with a DNS that understands what they are and what they are supposed to be doing.

The key-value store is also going to come in handy when it comes to deploying some nontrivial applications on this cluster. The first candidate in line for this is to move my local Vault storage from the disk of the Pi it’s running on to the distributed key-value store provided by Consul.

Tools and methods

Starting with empty machines, I began to think about best way for me to get to these goals. If I were making something in the real (physical) world, from coarse materials, I would probably first sit down to draw plan or sketch of what I wanted to achieve, then try to conceive of the steps needed to get from there to final design.

Which cuts would I need to make? What joins would be necessary? Which parts would need to move and by how much?

Most importantly, do I have the right tools for the job?

I’ve often had to attempt work without the right tools for the job and although it has seldom been a disaster, the experience has always left me somewhat frustrated. This time, it’s personal, so I want to choose tools that suit me, as well as get the job done elegantly.

Base platform

Right off the bat, I think it’s useful to separate the stages of “initial state” from “changing state”. Bootstrapping a system to a desired initial state often involves a catch-22 though.

Where an environment already offers providers, in the Terraform sense, bootstrapping is no problem; one declares desired state, generates and applies a plan.

In my case however, I don’t have a provider, I merely have ssh endpoints which I can access, so my instinct was to write an Ansible playbook to bring the barren desert before me to a desired configuration state. I was wary throughout the process of creating the new role and playbook of not letting the Ansible scope creep into state management as it’s intended in the Terraform sense. There doesn’t yet seem to be a natural line where Ansible should stop and Terraform should take over, but I can say with some certainty that I wanted some code to take an arbitrary empty instance and put a consul agent on it.

The atomic role should be re-usable, idempotent and take into account the intended function of the instance, with just enough knowledge of my inventory, not more.

While writing that inventory, I had the comforting feeling of knowing exactly which things I was talking about, since I could actually look directly at them in my office, rather than having to consider some abstract idea of a “machine in pool in a datacentre”. Clearly, this cannot scale, but it was a nice sense of nostalgia!

Nonetheless, this digression may serve to illustrate how I wanted to organise the resources - physical things would be assigned roles in my Consul cluster, rendering the vague image clearer:

- The Pi-3s and 4s would be servers and one of them would be elected leader

- The Pi 4 would be the UI

- The Pi-Zeros would be members

Since I had a clear mapping between thing and address on the network, I could organise them neatly in my inventory for now. I do suspect that I’m missing some concept which will help me later when this categorisation fails to scale further, but I had a good enough place to start.

Just enough Ansible

Following the

Consul deployment guide,

I wrote the

Ansible role

in my monorepo. With a few boolean variables to define what role a target had

(i.e: is_server, is_ui, default to False), I could run the playbook

- name: Deploy Consul

hosts: consul_agents

roles: - consulThree templates were needed

- systemd unit to start the service

consul.hclto configure consul agentserver.hclwhen the object was designated to act as a server

To generate the consul.hcl configuration for example, we make use of a few

defaults and the booleans referred to before:

datacenter = "{{ data_centre }}"

data_dir = "/opt/consul"

encrypt = "{{ gossip_key }}"

ca_file = "/etc/consul.d/consul-agent-ca.pem"

{% if (is_server | default('false')) | bool %}

cert_file = "/etc/consul.d/dc1-server-consul-0.pem"

key_file = "/etc/consul.d/dc1-server-consul-0-key.pem"

{% else %}

cert_file = "/etc/consul.d/dc1-client-consul-0.pem"

key_file = "/etc/consul.d/dc1-client-consul-0-key.pem"

{% endif %}

verify_incoming = true

verify_outgoing = true

verify_server_hostname = true

retry_join = {{ join_cidr | to_json }}

# Enable Consul ACLs

acl = {

enabled = true

default_policy = "allow"

enable_token_persistence = true

}The certificates and keys are generated by Ansible tasks locally before

distributing them to their targets, again depending on the role. One tricky part

which I haven’t quite figured out yet is how to get the agents to join the

cluster with zero-knowledge. I’ve cheated a bit passing what seems like a

variable (join_cidr) to the template, when in fact, what’s passed is an array

with a single IP – the Pi4 which I know I want to be leader of the cluster.

This is clearly not the right way to go about doing things, but I still need to

get the hang of bootstrapping a datacentre.

Lol, datacentre! It’s literally a few raspberry pis!

With just enough Ansible (315 LOC), we have a cluster which we can Terraform:

Success of a kind!

Now that we’ve found Consul, what are we going to do with it?

Hopefully, next I will be Terraforming Consul to deploy services, and moving on to the next big unknown in the Hashi stable: Nomad.